Maternal Mortality Racial Disparities

- Black women are more than 3 times likely to die from pregnancy related conditions, maternal mortality, than are Asian, Latinx, and White women.1

- Maternal mortality rates for Black women over

the age of 30 are 4 to 5 times higher than the rates for White women.2

the age of 30 are 4 to 5 times higher than the rates for White women.2 - Maternal mortality rates are rising, and Black women show the fastest rate of increase.1

- Sixty-percent4 of maternal mortality deaths are preventable.

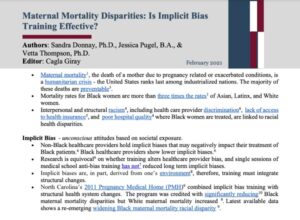

Maternal Mortality, death of a mother due to pregnancy related or exacerbated conditions within 12 months of delivery, is a humanitarian crisis such that rates in the United States have increased in the past 20 years2. The U.S. now ranks last in mortality rates among industrialized nations.5 Maternal mortality rates for Black women are more than 3 times those of other ethnic-racial groups, and for Black mothers over age 30, this disparity is four to five times that of Whites. 2 These disparities persist across socioeconomic levels in that Black college graduates show more than 5 times the maternal mortality rates as Whites.2 When considering the medical causes of mortality, cardiovascular disease, including hypertension and congestive heart failure, amniotic fluid embolisms, pulmonary embolisms, and cerebrovascular accidents, are implicated among the most frequent. 4.

Maternal morbidity, a “near miss” of mortality, defined as having an unplanned outcome of labor and delivery resulting in adverse short or long-term maternal consequences, has similarly been rising in the U.S., impacting about 50,000 women annually7. Black women are also at the highest risk for severe maternal morbidity when compared with women from other ethnic-racial groups.8 Data show that 60% of mortalities and a majority of morbidities are preventable.4

Structural and interpersonal factors are suggested as contributors to these disparities. For example, lack of access to health insurance may result in women with underlying health conditions going undetected until giving birth6, 2) poor hospital quality where Black women are more likely to be treated3 can lead to lower quality of care, and 3) racial discrimination by health care providers can similarly lead to lower quality of care for Black women when they deliver in the same hospital as Whites.3

Interventions include the Centers for Disease Control’s (CDC’s) funding for the establishment and expansion of state-wide Maternal Mortality Review Committees (MMRCs) that are charged with collecting, standardizing, and disseminating morbidity and mortality data.2. MMRCs are also charged with developing effective interventions.2 Federal legislation introduced in the senate (e.g., senate bill #s 1343 and 3424) include Medicaid extension of maternal benefits from 2 to 12 months postpartum; state funding for the development of demonstration projects to provide personalized care for Medicaid eligible at risk mothers; funding for community outreach; implicit bias training for health care professionals, and interventions to diversify the perinatal health care sector. This section will examine the status and effectiveness of interventions offer evidence – based solutions.

- Howell, E. (2018). Reducing disparities in severe maternal morbidity and mortality. Clinical Obstetrics and Gynecology, 61, 387-399.

- Center for Disease Control, (2019). Racial and Ethnic Disparities Continue in Pregnancy Related Deaths: Black, American Indian/Alaska Native women most affected. Retrieved January 27, 2021, from: https://www.cdc.gov/media/releases/2019/p0905-racial-ethnic-disparities-pregnancy-deaths.html.

- Howell, E. & Zeitlin, J. (2017). Improving Hospital Quality to Reduce Disparities in Severe Maternal Morbidity and Mortality. Seminars in Perinatology, 41, 266-272.

- Center for Disease Control, (2019). Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. September 6, 2019. Retrieved January 27, 2021, 68(35);762–765 from: https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/68/wr/mm6835a3.htm?s_cid=mm6835a3_w.

- Tikkanen, R., Gunja, M., & Zephyrin, L. (2020). Maternal Mortality and Maternity Care in the United States Compared to 10 Other Developed Countries. The Commonwealth Fund. Retrieved January 27, 2021, from https://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/issue-briefs/2020/nov/maternal-mortality-maternity-care-us-compared-10-countries.

- Lister, R. Drake, W., Scott, B.H., Graves, C. (2019). Black maternal mortality – The elephant in the room. World Journal of Gynecological and Women’s Health, 3, 1-4. doi: 10.33552/wjgwh.2019.03.000555

- Centers For Disease Control (2020) Reproductive Health Severe maternal morbidity in the United States. Retrieved 1.27.2, from: https://www.cdc.gov/reproductivehealth/maternalinfanthealth/severematernalmorbidity.html.

- Gray, K.E., Wallace, E.R., Nelson, K.R., Reed, SD, Schiff, M.A. (2012). Population-based study of risk factors for severe maternal morbidity. Paediatric Perinatal Epidemiology, 26, 506-514. doi: 10.1111/ppe.12011